May 1, 2023

Prashanth Ramakrishna

The Sumcheck Protocol (SCP) is an interactive proof that allows a prover $\mathcal{P}_{sc}$ to convince a verifier $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ that some multivariate polynomial $p$ with coefficients from finite field $\mathbb{F}$ yields a claimed value $T$ when its evaluations are summed over the boolean hypercube $\lbrace 0,1 \rbrace^{w}$. Over the past several years the power of SCP has become incredibly pivotal in the development of general purpose zero-knowledge proof systems, in both the univariate and multivariate cases. At the heart of many of these systems is an Interactive Oracle Proof (IOP) whose attractive efficiency guarantees rely on creative applications of various SCP variants. In this post, we will introduce the original SCP. This will serve as a foundation for understanding IOP constructions more generally.

More formally, the SCP proof $\Pi_{sc}$ consists of the interactive sumcheck prover-verifier pair $(\mathcal{P}_{sc}, \mathcal{V}_{sc})$ along with a protocol context describing the sumcheck statement. To specify this context, we refer to the sumcheck instance $\mathbb{I}_{sc} = (\mathbb{F}, p, T)$, where $p \in \mathbb{F}[\vec{X}]$ is characterized by its number of variables $w$ and total degree $\mathsf{deg}(p) = d$. Recall that $\mathsf{deg}(p)$ denotes the maximum sum of powers in a single monomial term of $p$. In contrast, we refer to $d_{i} = \mathsf{deg}_{i}(p)$ as the degree of $p$’s $i$-th variable. We associate a sumcheck instance with a sumcheck statement that $\mathcal{P}_{sc}$ proves to $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$. Treating $p$ as the witness, we say that $\mathbb{I}_{sc}$ is in language $\mathcal{L}_{sc}$ if the associated sumcheck statement is indeed true.

$$ \begin{equation} T \overset{c}{=} \sum_{x_{1} \in \lbrace 0,1 \rbrace} \sum_{x_{2} \in \lbrace 0,1\rbrace} \ldots \sum_{v_{w} \in \lbrace 0,1\rbrace} p(x_{1}, \dots, x_{w}). \end{equation} $$

For the sake of brevity, let $\mathcal{B}^{w}$ denote $w$-dimensional boolean hypercube, allowing us to rewrite the above as

$$ \begin{equation} \mathbb{I}_{sc} = (\mathbb{F}, p, T) \Longleftrightarrow T \overset{c}{=} \sum_{\vec{x} \in \mathcal{B}^{w}} p(\vec{x}). \end{equation} $$

Fully, we say that given $\mathbb{I}_{sc} \in \mathcal{L}_{sc}$, $\Pi_{sc}(\mathbb{I}_{sc})$ succeeds if $\mathcal{P}_{sc}$ is able to convince $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ of $\mathbb{I}_{sc}$’s corresponding claim. Clearly, one way for $\mathcal{P}_{sc}$ to proceed is by simply summing the evaluations of $p$ over $\mathcal{B}^{w}$ then sending his result $T$ to $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$. $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$, who has a description of $p$, can check $\mathcal{P}_{sc}$’s work by redoing the computation and obtaining his own result $T’$. $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ accepts if and only if $T’ = T$. However, this costs $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ $O(2^{w})$ evaluations of $p$, exponential in the number of $p$’s variables. Ideally, we wish to harness the power of interaction in order to alleviate nearly all of the burden on $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$. Indeed, we will see not only that there exists a $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ linear in $w$, but also that the above sumcheck statement can be generalized to many different settings.

The main idea behind the SCP is that $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ can delegate work to $\mathcal{P}_{sc}$ by using randomly sampled elements from $\mathbb{F}$ to incrementally fix the variables of $p$. In each round, $\mathcal{P}_{sc}$ sends a univariate polynomial distilled from $p$ in the following way. Variables fixed in previous rounds remain fixed and $\mathcal{P}_{sc}$ sums $p$ over the remaining free dimensions of $\mathcal{B}^{w}$. $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ dilligently performs continuous checks to verify consistency between polynomials received in the last round and the current one. After $w$ rounds, she is left to evaluate $p$ at a single point in $\mathbb{F}^{w}$ consisting of the random elements previously sampled.

Cleanly describing the protocol requires clearly differentiating between variables fixed with randomness, the variable being isolated in the current round, and the still free variables that will be dissolved by the prover. $r_{i}$ denotes the verifier sampled field element in round $i$ and $\vec{r}_{i} = \langle r_{1}, \dots, r_{i} \rangle$ correspondingly gives the list of verifier sampled field elements since the beginning of the protocol. $\vec{r_{i}}$ can also be thought of as variables $X_{1}, \dots, X_{i}$ fixed with verifier randomness. $X_{i}$ is the free variable for the univariate polynomial computed and sent by $\mathcal{P}_{sc}$ in round $i$, while $\vec{x}_{i+1} = \langle X_{i+1}, \dots, X_{w} \rangle$ represents the variables that are “collapsed” in round $i$ by partial summation. In each round $w-1$ variables are either fixed with verifier randomness or collapsed via partial summation. Lastly, we refer to individual degree $\mathsf{deg}_{i}(p)$ as the maximum power of $p$’s $i$th variable.

$$ \begin{aligned} &\textbf{Round 1.} && &&\\ &\mathcal{P}_{sc} &&\text{Channel} &&\mathcal{V}_{sc}\\ &p_{1}(X_{1}) = \displaystyle{\sum_{\vec{x}_{2} \in \mathcal{B}^{w-1}} p(X_{1}, \vec{x}_{2})} &&\overset{p_{1}}{\longrightarrow} &&\mathsf{check_{1}}: p_{1}(0) + p_{1}(1) = T\\ & && &&\mathsf{check_{2}}: \mathsf{deg}(p_{1}) \le \mathsf{deg}_{1}(p)\\ & &&\overset{r_{1}}{\longleftarrow} &&r_{1} \overset{\text{\textdollar}}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{F}\\ &\textbf{Round 2.} && &&\\ &p_{2}(X_{2}) = \displaystyle{\sum_{\vec{x_{3}} \in \mathcal{B}^{w-2}} p(r_{1}, X_{2}, \vec{x_{3}})} &&\overset{p_{2}}{\longrightarrow} &&\mathsf{check_{1}}: p_{2}(0) + p_{2}(1) = p_{1}(r_{1})\\ & && &&\mathsf{check_{2}}: \mathsf{deg}(p_{2}) \le \mathsf{deg}_{2}(p)\\ & &&\overset{r_{2}}{\longleftarrow} &&r_{2} \overset{\text{\textdollar}}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{F}\\ &\textbf{Round $\bm{2 \le i < w}$.} && &&\\ &p_{i}(X_{i}) = \displaystyle{\sum_{\vec{x}_{i+1} \in \mathcal{B}^{w-i}} p(\vec{r}_{i-1}, X_{i}, \vec{x}_{i+1})} &&\overset{p_{i}}{\longrightarrow} &&\mathsf{check_{1}}: p_{i}(0) + p_{i}(1) = p_{i-1}(r_{i-1})\\ & && &&\mathsf{check_{2}}: \mathsf{deg}(p_{i}) \le \mathsf{deg}_{i}(p)\\ & &&\overset{r_{i}}{\longleftarrow} &&r_{i} \overset{\text{\textdollar}}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{F}\\ &\textbf{Round $\bm{w}$.} && && \\ & p_{w}(X_{w}) = p(\vec{r_{w-1}}, X_{w}) && \overset{p_{w}}{\longrightarrow} &&\mathsf{check_{1}}: p_{w}(0) + p_{w}(1) = p_{w-1}(r_{w-1})\\ & && && \mathsf{check_{2}}: \mathsf{deg}(p_{w}) \le \mathsf{deg}_{i}(p) \\ & && && r_{w} \overset{\text{\textdollar}}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{F} \\ & && && \mathsf{check_{final}}: p_{w}(r_{w}) = p(\vec{r_{w}}) \\ & && && \text{Return 1 iff checks pass} \\ \end{aligned} $$

Though the conceit of the protocol is intuitive enough – using randomness to recursively fix variables allows for round complexity linear in $w$ – there is some hidden machinery here that should be discussed.

Polynomial Descriptions. The SCP is agnostic to the description $\mathcal{P}_{sc}$ chooses for each $p_{i}$ he sends. However, in practice, one has the choice to implement this description as either coefficient or evaluation form. Recall that the latter follows from the fact that each $p_{i}$ is a univariate polynomial and can therefore be specified by $\mathsf{deg}_{i}(p) + 1$ evaluations over $\mathbb{F}$, canonically be taken as the evaluations of $p_{i}$ on the set $[0, \mathsf{deg}(p_{i})+1] \subseteq \mathbb{F}$.Often, as will be seen shortly, we are interested in relatively low-degree polynomials and as such might enjoy a communication reduction only having to send $d_{i}$ field elements per round. Still, sending polynomials in evaluation form require interpolation from the verifier before evaluatng each $p_{i}(r_{i})$. If optimizing for verifier efficiency, one would have the prover interpolate, reducing verifier work in the first $w-1$ rounds only to sampling random field elements and evaluating univariate polynomials on them.

Why $\mathsf{check_{2}}$ matters. Clearly, $\mathsf{check_{1}}$ exists to ensure consistency between polynomials sent in consecutive rounds. At first glance however, $\mathsf{check_{2}}$ seems redundant, since $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ can simply inspect the length of the RS codeword sent in each round. Keep in mind, though, that the above protocol is written with some level of versatility in mind. The purpose of $\mathsf{check_{2}}$ is for $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ to determine the message she recieves in a particular round is valid. In this case, the enforcement mechanism is a low-degree test that $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ is assumed to have access to. However, in other settings the enforcement mechanism may be an alternate form of proximity test for a different code. Additionally, when pursuing zero-knowledge, messages may be committed to, in which case $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ may require yet another enforcement mechanism that either follows from or integrates with the commitment scheme in use to ensure the validity of the underlying polynomial encoding.

Costing $\mathsf{check_{final}}$. Assume that verifier has oracle access to the $p$.

The sumcheck protocol can be generalized to any subset $S \subset \mathbb{F}$ in the straightforward way by replacing $\mathcal{B}^{w}$ with $S^{w}$. In round $1$, the prover must compute the partial sum $p_{1} = \sum_{\vec{x}_{2} \in s^{w-1}} p(X_{1}, \vec{x}_{2})$ and the verifier must accodingly check that $\sum_{s \in S}p_{1}(s) = T$. In general, the only modification is that for round $i$, $\mathsf{check_{1}}$ asserts $$\sum_{s \in S}p_{i}(s) = p_{i-1}(r_{i-1})$$ The verifier’s work increases expectedly by a constant factor.

The power of the SCP comes from (1) it’s attractive efficiency metrics, allowing a seemingly expensive computation to be verified with relatively little work while only imposing a minor overhead to a prover implementing the best strategy to actually perform the computation (which, of course, must be done by some party at some point) and (2) the fact that a wide array of problems can naturally be cast as sumcheck instance. These two facts make the SCP an incredibly versatile and indespensible tool and encourage one to develop a sumchecky worldview. In this section, I’ll briefly discuss the complexity of the SCP as well as the standard security properties of completeness and soundness.

Complexity. First, let’s consider $\mathcal{P}_{sc}$. In each of the $w$ rounds, he must compute a partial sum of $p$ over a boolean hypercube of reduced dimensionality. This ammounts to $\sum_{i = 1}^{w} |\mathcal{B}^{i}| = 2^{w+1}$ evaluation of $p$, only a constant factor more than the work of summing the evaluations of $p$ over $\mathcal{B}^{w}$. He must then evaluate the resulting univariate polynomials on $\mathsf{deg}_{i}(p) + 1$ points from $\mathbb{F}$ for each round $i$, resulting in $w + \sum_{i = 1}^{w} \mathsf{deg}_{i}(p)$ number of evaluations and field elements that $\mathcal{P}_{sc}$ communicates throughout the protocol. still need to discuss prover space

Next, we consider $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$, who’s work is neatly characterized by $w$ applications of $\mathsf{check_{1}}$ and $\mathsf{check_{2}}$, followed by a single application of $\mathsf{check_{final}}$.

| Prover Runtime | Prover Space | Prover Communication | Verifier Runtime | Verifier Space | Verifier Communication | Round Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $O(2^{w})$ | $O(n)$ | $O(w)$ | $O(n)$ | $O(n)$ | $O(d)$ | $O(d)$ |

Space should matter for resource constrained devices. Where are sumchecks actually getting used?

Completeness. Recall that completeness requires that if $\mathbb{I}_{sc} \in \mathcal{L}_{sc}$, then $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ will accept with probability 1. In the context of the SCP, this means that $\mathsf{check_{1}}$ and $\mathsf{check_{2}}$ pass in every round and $\mathsf{check_{final}}$ passes in the final round. The proof can be constructed inductively on the number of $p$’s variables. In the base case, $p$ will be a constant function. If $p = T$, then $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ will accept. Next, all that one needs to show is that a valid sumcheck instance for a polynomial with $w > 0$ variables can be reduced to a valid sumcheck instance for a polynomial with $w-1$ variables.

Soundness. Amazingly, nearly all of the security of PIOP-based proof systems is derived from a single lemma, whose ubiquity cannot be overstated: the Shwartz-Zippel lemma, a probabilistic tool for polynomial zero testing and, consequently, identity testing – given $p_{1}, p_{2} \in \mathbb{F}[\vec{X}]$ of the same total degree, testing whether $p_{1} = p_{2}$ is equivalent to testing whether $p_{1} - p_{2} = p_{3} = 0$.

Shwartz-Zippel Lemma (SZL): Let $p \in \mathbb{F}[X_{1}, \dots, X_{w}]$ be a non-zero $w$-variate polynomial over field $\mathbb{F}$. Further, let $S \subseteq \mathbb{F}$ be a finite subset of $\mathbb{F}$. Then the probability that $p$ evaluates to $0$ on some uniformly random point $\vec{r} \in S^{w}$ is given by

$$\Pr[p(r_{1}, \dots, r_{w}) = 0] \le \frac{d}{\lvert S \rvert}$$

Recall that soundess error $\varepsilon_{sc}$ aims to capture the probability that a cheating prover $\tilde{\mathcal{P}_{sc}}$ with an invalid sumcheck instance $\tilde{\mathbb{I}}_{sc} = (\mathbb{F}, \tilde{p}, T) \not\in \mathcal{L_{sc}}$ will succeed. $\varepsilon_{sc}$ is given by,

$$\begin{equation}\varepsilon_{sc} \le \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{w}\mathsf{deg}_{i}(p)}{|\mathbb{F}|}\end{equation}$$.

The proof again proceeds inductively on $w$, but can be seen intuitively since, by SZP, there are at most $\frac{d}{\mathbb{F}}$ points $r_{i}$ that $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ can sample in round $i$ for which $\tilde{\mathcal{P}_{sc}}$’s malicious polynomial $\tilde{p}_{i}(r_{i}) = p_{i}(r_{i})$ and will therefore pass $\mathsf{check_{1}}$ and $\mathsf{check_{2}}$. The number of rounds being $w$ results in the given bound for $\varepsilon_{sc}$ for a $\tilde{\mathcal{P}}_{sc}$’s sucess. Note that a protocol is considered sound if $\varepsilon$ is sufficiently small, usually with respect to some security parameter. This requires choosing a big enough $\mathbb{F}$. In general, it is good enough to choose $|\mathbb{F}| = O(\mathsf{poly}(|\mathcal{B}^{w}|))$.

The sumcheck protocol is easily extended to the sumcheck for a batch of polynomials $\lbrace p_{i}\rbrace$ for $i \in [0,L]$ by letting the verifier sample a random vector $\vec{\lambda} \in \mathbb{F}^{L}$, and a subsequent sumcheck protocol for the random linar combination $$\hat{p}(\vec{X}) = p_{0}(\vec{X}) + \sum_{i = 1}^{L} \lambda_{i} \cdot p_{i}(\vec{X}).$$ The soundness error increases only slightly $$\varepsilon_{bsc} \le \frac{1 + \sum_{i = 1}^{w}\mathsf{deg}_{i}(p_{i})}{|\mathbb{F}|}$$

Theoretical Relevance of SCP and Connection to Coding.

The Tensor Sumcheck is originally developed in order to provide alternate proof of the IP Theorem. This alternate proof establishes the intuition that resorting to algebra in classical proofs of the IP Theorem is useful because low-degree polynomials are good error correcting codes, and encoding the truth table of quantifiable boolean formulas allows a verifier to decide satisfiability efficiently by simply querying a random coordinate of the resulting encoding.

The tensor product operation generalizes the process of moving from univariate polynomials to multivariate polynomials. Univariate polynomials can be viewed as error correcting codes. Multivariate polynomials can then be obtained by applying the tensor product oepration to univariate polynomials. Error correcting codes obtained via the tensor product operation are called tensor codes.

The SumCheck protocol works for multivariate polynomials, but in fact can work for any tensor code. Tensor codes have the following property: A code word $c$ of a tensor code can be viewed as a function from some hypercube $[\ell]^{m} \longrightarrow \mathbb{F}$ such that if a function $f$ is defined by summation of $c$ over the hypercube, then $f$ itself is a codeword of some other error-correcting code. That is, the property that makes $\Pi_{msc}$ function is that multivariate polynomials are tensor codes.

The alternate proof of the IP Theorem proceeds by replacing the polynomial obtained by arithmetization with a tensor codeword that agrees with the formula on the boolean hypercube. The replacement requires generalizing the arithmetization technique to work with general error correcting codes instead of just polynomials. This is done by constructing multiplication codes, error correcting codes that emulate polynomial multiplication.

Our generalization of the sum-check protocol says roughly the following: Let $c$ be a codeword of code $C^{m}$, and let $d$ be a codeword of a code $D^{m}$ that is consistent with the messy encoding by $c$. Then, the sum-check protocol reduces the task of verifying a claim of the form $c(\vec{i}) = u$ to the task of verifying a claim of the form $d(\vec{r}) = v$ (where $\vec{i}$ and $\vec{r}$ are coordinates of $c$ and $d$ respectively, and $u, v \in \mathbb{F}$).

Some Specific Use Cases of Varying Utility: To put in table form

Verifying Matrix Products

Verifying Scalar Products

Verifying Traingle Counts

Proving as Fast as Computing: Succinct Arguments with Constant Prover Overhead

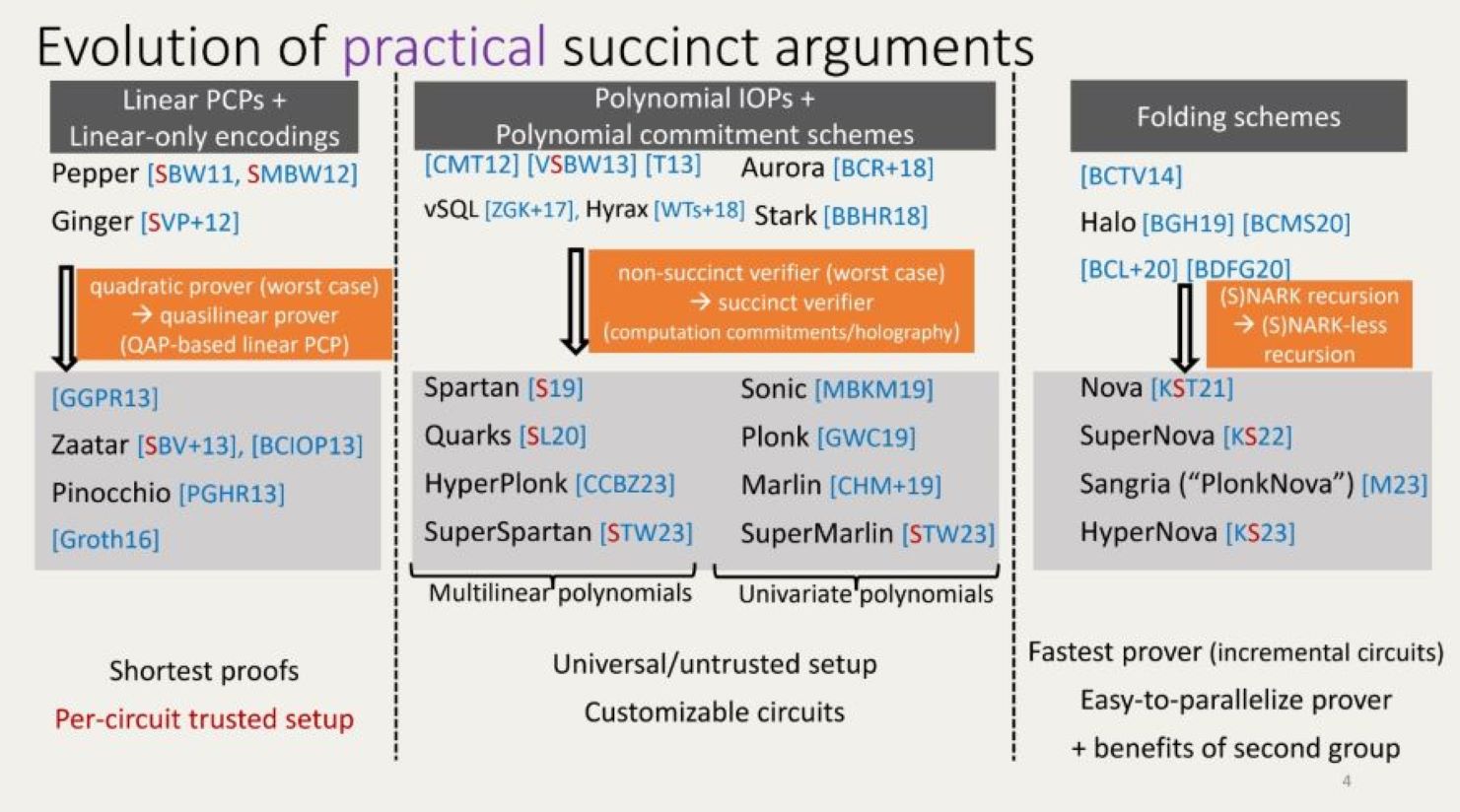

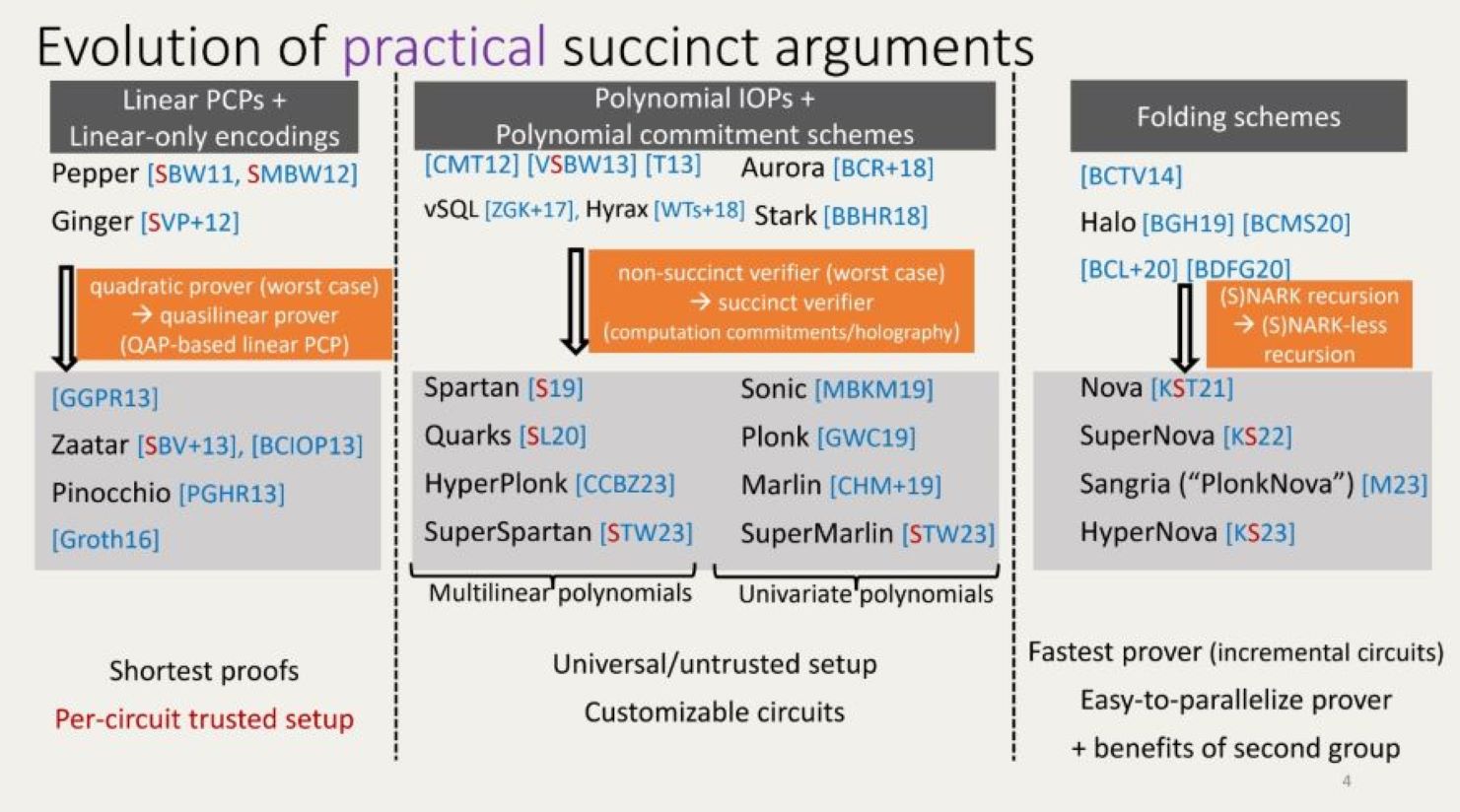

The SCP has been instrumental in developing succinct arguments of knowledge that can be augmented with zero-knowledge using cryptographic techniques. The image below, taken from slides developed by link talk Setty, summarizes three approximate eras (overlapping) of succinct argument constructions and, by extension, zero knowledge proof systems. Here, I will attempt to give an understanding of where sumcheck instances arise in the process of generating a zero knowledge proof and how they contribute to realizing efficiency.

Recall briefly the basic flow from computation to zero knowledge proof. A prover wishes to perform some computation $\mathsf{Comp}$ with input $\mathsf{Input}$ and produce a proof that his work is correct. $\mathsf{Comp}$ can be equivalently expressed as an algebraic circuit $\mathcal{C}$ with input $I_{\mathcal{C}}$. The circuit naturally represents a relation that defines a language $\mathcal{L}_{\mathcal{C}}$. Here, we will differentiate the private part of the relation as the input witness $I_{\mathcal{C}}$ and the public part as the circuit itself, $\mathcal{C}$. We say that $(\mathcal{C}, I_{\mathcal{C}}) \in \mathcal{L}_{\mathcal{C}}$ if $\mathcal{C}(I_{\mathcal{C}}) = 1$. There are a number of paths from this juncture to a zero knowledge proof. One can work directly over the circuit itself and produce a proof using a technique known as multiparty computation in-the-head (MPC-ITH). One can also proceed through various methods of arithmetization that translate $\mathcal{C}$ from a circuit to a constraint system and $I_{\mathcal{C}}$ to a satisfying assignment for the system. Zero-knowledge is then achieved by cryptographically commiting to an assignment, then arguing that the opening of the commitment (i.e, the assignment contained within) is indeed satisfying. I will focus here on the popular Rank One Constraint System (R1CS), which takes $\mathcal{C}$ to a set of public coefficient matrices $A, B, C \in \mathbb{F}^{n \times n}$ and $I_{\mathcal{C}}$ to an assignment $\vec{z} \in \mathbb{F}^{n}$. Recall that $\mathbb{I}_{\mathsf{R1CS}} = ((A,B,C), \vec{z}) \in \mathcal{L}_{\mathsf{R1CS}}$ iff

$$\begin{equation} A\vec{z} \circ B\vec{z} = C\vec{z}. \end{equation}$$

Now, what is left is to transmute this statement, which is fundamentally one about the equality of vectors in $\mathbb{F}^{n}$, into one regarding polynomials – in particular, a sumcheck statement. This is the transformation which we subject to magnification and that has analogues across nearly all proof systems. Committing to $z$ allows for the possibility of realizing zero-knowledge in the “commit-and-prove” paradigm. The process described thus far can be visualized as follows:

$$(\mathsf{Comp}, \mathsf{Input})$$ $$\Updownarrow$$ $$(\mathcal{C}, I_{\mathcal{C}}) \longrightarrow \mathbb{I}_{\mathsf{R1CS}} \rightarrow \mathbb{I}_{sc}$$ $$\Updownarrow$$ $$\mathcal{L}_{\mathcal{C}} \longrightarrow \mathcal{L}_{\mathsf{R1CS}} \longrightarrow \mathcal{L}_{sc}$$

We will roughly follow the tack taken by Spartan, which in my view provides a natural insight into how the SCP is used in the construction of PIOP-based proof systems. At a high level, the transformation from an R1CS instance to a sumcheck instance consists of the following steps:

- Interpret matrix-vector and hadamard products as operations on functions over the boolean hypercube

- Transform the resulting statement into one regarding polynomials using multilinear extensions.

- Perform query reduction in order to obtain a sumcheck instance.

Let $s = \lceil\log(n)\rceil$. For any $n$-length vector, we can use an $s$-length binary string to index its entries. Alternatively, this can be thought of as unpacking indices (as field elements) into bits. Indeed a tensor of any dimensionality can be interpreted as as a map from the binary strings used to index an entry to the entry itself. As such, we consider the R1CS coefficient matrices and witness as the following maps:

$$A, B, C: \lbrace0, 1\rbrace^{s} \times \lbrace0,1\rbrace^{s} \longrightarrow \mathbb{F}$$ $$z: \lbrace 0,1 \rbrace^{s} \longrightarrow \mathbb{F}.$$

The R1CS relation can now be naturally expressed in the alternate interpretation as summations of functions evaluated over the $s$-dimensional boolean hypercube. $\forall (i, j) \in [1,n] \times [1, n]$ let $(\vec{x}, \vec{y}) \in \mathcal{B}^{s} \times \mathcal{B}^{s}$ be the corresponding binary unpacking. Then,

$$ \begin{aligned} & &&Az \circ Bz &&= Cz\\ &\implies &&\sum_{i \in [1,n]} \vec{a}_{i}z_{i} \circ \sum_{i \in [1,n]} \vec{b}_{i}z_{i} &&= \sum_{i \in [1,n]} \vec{c}_{i}z_{i} \\ &\implies &&\left[\left(\sum_{j\in[1,n]} a_{1j}z_{j} \times \sum_{j\in[1,n]} b_{1j}z_{j}\right), \dots, \left(\sum_{j\in[1,n]} a_{njz_{j}} \times \sum_{j\in[1,n]} b_{nj}z_{j}\right)\right]^{\bm{T}} &&= \left[\sum_{j\in[1,n]}c_{1j}z_{j}, \dots, \sum_{j\in[1,n]}c_{nj}z_{j}\right]^{\bm{T}}\\ &\implies &&\forall i \in [1,n], \left(\sum_{j\in[1,n]} a_{ij}z_{j}\right) \times \left(\sum_{j\in[1,n]} b_{ij}z_{j}\right) &&= \sum_{j\in[1,n]}c_{ij}z_{j}\\ &\implies &&\forall \vec{x} \in \mathcal{B}^{s}, \left(\sum_{\vec{y}\in\mathcal{B}^{s}}A(\vec{x},\vec{y})z(\vec{y})\right) \times \left(\sum_{\vec{y}\in\mathcal{B}^{s}}B(\vec{x},\vec{y})z(\vec{y})\right) && =\sum_{\vec{y}\in\mathcal{B}^{s}}C(\vec{x},\vec{y})z(\vec{y})\\ \end{aligned} $$

Next, we transform our relation regarding matrix maps into a relation regarding polynomials and in doing so, inch closer to a sumcheckable statement. To do so, we take the unique multilinear extensions of maps $A, B, C, Z$, denoted $\tilde{A},\tilde{B}, \tilde{C}, \tilde{z}$. Recall that a multilinear polynomial is a polynomial whose individual degree is at most one in each variable and that every $w$-variate function $f$ has a unique multilinear extension $\tilde{f}$ that agrees with $f$ on $\mathcal{B}^{w}$ but whose full domain is $\mathbb{F}$. Rephrasing our statement using multilinear extensions, we have

$$\forall x \in \mathcal{B}^{s}, \tilde{F}(\vec{x}) = \left(\sum_{\vec{y}\in\mathcal{B}^{s}}\tilde{A}(\vec{x},\vec{y})\tilde{z}(\vec{y})\right)\left(\sum_{\vec{y}\in\mathcal{B}^{s}}\tilde{B}(\vec{x},\vec{y})\tilde{z}(\vec{y})\right) - \sum_{\vec{y}\in\mathcal{B}^{s}}\tilde{C}(\vec{x},\vec{y})\tilde{z}(\vec{y}) = 0.$$

Still, however, the original R1CS statement has not been recast in sumcheckable form. Indeed what we are aming for is a claim about the summation of evaluations on $\tilde{F}$. Here, we can deploy a trick known as query reduction that will make use of the MLE basis polynomial

$$\begin{equation} \tilde{\mathsf{eq}}(\vec{x}, \vec{t}) = \prod_{i = 1}^{s} x_{i}t_{i} + (1 - x_{i})(1 - t_{i}). \end{equation}$$

The utility of $\tilde{\mathsf{eq}}$ stems from the fact that when $\vec{x} = \vec{e} \in \mathcal{B}^{s}$, $\tilde{\mathsf{eq}} = 1$ and when $\vec{x} \ne \vec{e}$, $\tilde{\mathsf{eq}} = 0$. Consider the following polynomial $Q: \mathbb{F}^{s} \rightarrow \mathbb{F}$ defined

$$\begin{equation} Q(\vec{t}) = \sum_{\vec{x} \in \mathcal{B}^{s}} \tilde{F}(\vec{x})\tilde{\mathsf{eq}}(\vec{x}, \vec{t}). \end{equation}$$

Notice first that by the special properties of $\tilde{\mathsf{eq}}$ we can claim that $Q = 0$ implies, via $\tilde{F}$, that $\vec{z}$ is a satisfying $\mathsf{R1CS}$ assignment.

Claim: $\tilde{F}(\vec{x}) = 0 \medspace \forall \vec{x} \in \mathcal{B}^{s}$ if and only if $Q(\vec{t}) = 0 \medspace \forall \vec{t} \in \mathbb{F}^{s}$.

$(\implies)$: Suppose $\forall \vec{x} \in \mathcal{B}^{s}$, $\tilde{F}(\vec{x}) = 0$. Further, let $\vec{t} \in \mathbb{F}^{s}$. Then, either (1) $\vec{t} \in \mathcal{B}^{s}$ or (2) $\vec{t} \in \mathbb{F}^{s}\backslash \mathcal{B}^{s}$. If (1), then $\tilde{\mathsf{eq}}(\vec{t}, \vec{x}) = 0 \medspace \forall \vec{x} \in \mathcal{B}^{s}$ and thus $Q(\vec{t}) = 0$. If (2), then $Q(\vec{t}) = \tilde{F}(\vec{t}) = 0$ by assumption.

$(\impliedby)$: Suppose $Q(\vec{t}) = 0 \medspace \forall \vec{t} \in \mathbb{F}^{s}$. Then $\forall \vec{x} \in \mathcal{B}^{s}$, either $\tilde{F}(\vec{x}) = 0$ or $\tilde{\mathsf{eq}}(\vec{x}, \vec{t}) = 0$. Let $\vec{t} \in \mathcal{B}^{s}$. Then, $Q(\vec{t}) = \tilde{F}(t) = 0$ by assumption. $\square$

This fact allows us to construct a sumcheck instance $\mathbb{I}_{sc}^{\mathsf{QRed}}$ on the query reduced polynomial $\tilde{F}(\vec{x})\tilde{\mathsf{eq}}(\vec{x},\vec{t})$ where $\vec{t}$ is fixed as randomly sampled $\tau \overset{\text{\textdollar}}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{F}^{s}$:

$$\mathbb{I}_{sc}^{\mathsf{QRed}} = (\mathbb{F}, p = \tilde{F}(\vec{x})\tilde{\mathsf{eq}}(\vec{x}, \tau), T = 0) \Longleftrightarrow 0 \overset{c}{=} \sum_{\vec{x} \in \mathcal{B}^{s}}\tilde{F}(\vec{x})\tilde{\mathsf{eq}}(\vec{x}, \tau) = Q(\tau).$$

We conclude that if $\Pi_{sc}(\mathbb{I}_{sc}^{\mathsf{QRed}}, \mathcal{P}_{sc}, \mathcal{V}_{sc})$ is invoked and $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ accepts it must be the case that

$$\mathbb{I}_{sc}^{\mathsf{QRed}} \in \mathcal{L}_{sc} \implies Q(\tau) = 0 \implies \tilde{F}(\vec{x}) = 0 \medspace \forall \vec{x} \in \mathcal{B}^{s} \implies A\vec{z} \circ B\vec{z} = C\vec{z}.$$

Accordingly, we can construct an interactive argument of knowledge for $\mathsf{R1CS}$ which ammounts to little more than running the SCP. Let $(\mathcal{P}, \mathcal{V})$ denote the $\mathsf{R1CS}$ prover-verifier pair that will call $(\mathcal{P}_{sc}, \mathcal{V}_{sc})$ at the appropriate time. $\mathcal{P}$ and $\mathcal{V}$ both receive $\mathbb{I}_{\mathsf{R1CS}}$. Call this argument $\Pi_{\mathsf{R1CS}}$

- $\mathcal{P}$ computes $\tilde{A}, \tilde{B}, \tilde{C}, \tilde{z}$

- $\mathcal{P}$ computes $\tilde{F}$

- $\mathcal{P}$ computes $G(\vec{x}, \vec{t}) = \tilde{F}(\vec{x})\tilde{\mathsf{eq}}(\vec{x}, \vec{t})$

- $\mathcal{V}$ samples $\tau \overset{\text{\textdollar}}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{F}^{s}$ and sends $\tau$ to $\mathcal{P}$

- $\mathcal{P}$ computes $G_{\tau}(\vec{x}) = \tilde{F}(\vec{x})\tilde{\mathsf{eq}}(\vec{x}, \tau)$

- $\mathcal{P}$ and $\mathcal{V}$ invoke $\mathcal{P}_{sc}$ and $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ respectively to interactively run $\Pi_{sc}$ on $\mathbb{I}_{sc}^{\mathsf{QRed}} = (\mathbb{F}, G_{\tau}, 0)$.

- If $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ accepts, then $\mathcal{V}$ also accepts. Otherwise, $\mathcal{V}$ rejects.

The relevant soundness error follows directly from the SZL. We are interested in the probability that $Q(\tau) = 0$ given that $\tilde{F}(\vec{x}) \ne 0 \medspace \forall \vec{x} \in \mathcal{B}^{s}$ and $\tau \overset{\text{\textdollar}}{\leftarrow} \mathbb{F}^{s}$. This is because if $\exists \vec{x} \in \mathcal{B}^{s}$ such that $\tilde{F}(\vec{x}) \ne 0$ then $z$ is not a satisfying assignment. Again, the soundess error captures the probability that a cheating prover with a non-satisfying assignment will succeed in tricking the verifier into accepting. We begin by assuming such a point exists, which we refer to as $\hat{\vec{x}}$. It follows that $Q(\hat{\vec{x}}) = \tilde{F}(\hat{\vec{x}}) \ne 0$ and $Q$ is therefore not the zero polynomial. This allows us to apply SZL to $Q$ and conclude that

$$\begin{equation}\varepsilon_{\mathsf{\tau}} = \Pr[Q(\vec{t}) = 0] \le \frac{s}{|\mathbb{F}|}. \end{equation}$$

In other words, the probability that $\mathcal{V}$ chooses a bad $\tau$ such that $Q(\tau) = 0$ even if $\vec{z}$ is not satisfying is bounded by $\frac{s}{|\mathbb{F}|}$. Further observe that because $\tilde{F}$ is quadratic and $\tilde{\mathsf{eq}}$ is linear, $\mathsf{deg}(\tilde{F}\cdot\tilde{\mathsf{eq}}) = 3$. Returning to the mechanics of the SCP, by our previous analysis, we have that

$$\begin{equation} \varepsilon_{sc} = \Pr[\mathcal{V}_{sc} = 1 \mid Q(\tau) \ne 0] \le \frac{3s}{|\mathbb{F}|}. \end{equation}$$

The soundness error for the full protocol $\Pi_{\mathsf{R1CS}}$, denoted $\varepsilon_{\mathsf{R1CS}}$, is determined over the $\mathcal{V}$’s choice of $\tau$ and $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$’s choice of $r_{i}$ in each round of $\Pi_{sc}$. Suppose $\vec{z}$ is not satisfying. Then there are two possibilities. Either (1) $\mathcal{V}$ can choose a bad $\tau$, in which case $Q(\tau) = 0$ and $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ will accept or (2) $\mathcal{V}$ can choose a good $\tau$, in which case $Q(\tau) \ne 0$ and $\mathcal{V}_{sc}$ will only accept if he samples bad randomness throughout $\Pi_{sc}$. $\varepsilon_{\mathsf{R1CS}}$ is thus given by

$$\begin{equation}\begin{aligned} \varepsilon_{\mathsf{R1CS}} &= \Pr[\mathcal{V} = 1 \mid \mathbb{I}_{\mathsf{R1CS}} \not\in \mathcal{L}_{\mathsf{R1CS}}] \\ &= \Pr[\mathcal{V}_{sc} = 1 \mid Q(\tau) = 0 \land \mathbb{I}_{\mathsf{R1CS}} \not\in \mathcal{L}_{\mathsf{R1CS}}] + \Pr[\mathcal{V}_{sc} = 1 \mid Q(\tau) \ne 0 \land \mathbb{I}_{\mathsf{R1CS}} \not\in \mathcal{L}_{\mathsf{R1CS}}] \\ &= \varepsilon_{\tau} + (1-\varepsilon_{\tau})(\varepsilon_{sc}) \\ &\le \frac{4s|\mathbb{F}|-3s^{2}}{|\mathbb{F}|^{2}}. \end{aligned}\end{equation} $$

The cost of $\mathcal{V}$ consists of sampling $\tau$ and the work associated with $\Pi_{sc}$. Notice, however, that if $\mathcal{V}$ were to include a check that rejects if $Q(\tau) \ne 0$, the $\epsilon_{\mathsf{R1CS}}$ would collapse to $\epsilon_{\tau}$. However, this would require $\mathcal{V}$ to redo the work of $\mathcal{P}$ in steps 1-3 of $\Pi_{\mathsf{R1CS}}$. There is therefore a tradeoff between soundness and verifier efficiency that incurrs $\frac{3s(|\mathbb{F}| - s)}{|\mathbb{F}|^{s}}$ additional soundness error to avoid a polylogarithmic number of field operations in $n$.

Theoretical Relevance of SCP. IP = PSPACE, GKR Protocol, etc. etc. But don’t go too deep. No need to explain anything here.

Because the SCP is such a central component to modern proof systems, it is important to consider the efficiency of its implementation with respect to various hardware options. Sumcheck hardware acceleration is an understudied problem and represents an opportunity for further investigation. What’s interesting here is that the highly local nature of the memory retrievals for the prover actually make the SCP quite amenable to hardware acceleration. This is in contrast to FFTs, which are difficult to accelerate due to their highly non-local memory access pattern. This is one of the main arguments for why sumcheck-based proof systems are the best hope for concrete efficiency.

Memory Retrieval.

Hardware Optimizations.

So far, we have seen how succinct arguments can be built from multivariate polynomials. Currently though, the most concretely efficient proof systems are constructed not from multivariate polynomials but instead from univariate ones. And, where univariate polynomials are used, a univariate sumcheck is needed. The univariate sumcheck protocol $\Pi_{usc} = (\mathcal{P}_{usc}, \mathcal{V}_{usc})$ first appeared in Aurora for this very reason – that is, to verify univariate sumcheck instances of the form $\mathbb{I}_{usc} = (\mathbb{F}, H, f, \mu)$ that claim

$$\sum_{a \in H}f(a) \overset{c}{=} \mu.$$

Here, a summation domain $H \subseteq \mathbb{F}$ is specified. The only condition on $H$ is that it must be either an additive or multiplicative subgroup of $\mathbb{F}$. This restriction is necessary because $\Pi_{usc}$ relies on facts about polynomial summations over these domains. The development of such facts has, over time, corresponded to the expansion of sumcheck beyond the boolean hypercube and even finite fields.

Multiplicative Subgroup Summation Lemma (MSS). Let $H$ be a multiplicative subgroup of finite field $\mathbb{F}$. Further, let $f \in \mathbb{F}[ X]$ such that $\mathsf{deg}(f) < |H|$. Then,

$$\begin{equation}\sum_{a \in H} f(a) = f(0) \cdot |H|\end{equation}$$

If $f \in \mathbb{F}[X]$ such that $\mathsf{deg}(f) < |H|$, then it can be written as $f(X) = \sum_{i = 0}^{|H|-1} c_{i}X^{i}$ where $c_{0}, \dots, c_{1}$ are coefficients from $\mathbb{F}$. Summing over $H$, we can write $\sum_{a \in H}\sum_{i = 0}^{|H| - 1} c_{i}a^{i}$. Next, switching the order of summation, we have $\sum_{i = 0}^{|H|-1}\sum_{a \in H} c_{i}a^{i}$. Because $H$ is a multiplicative subgroup, it is cyclic, and its elements can be enumerated as powers of a root of unity $H = \langle \omega \rangle = \lbrace 1, \omega, \omega^{2}, \dots, \omega^{|H|-1} \rbrace$. As such, we rewrite our summation accordingly and simplify in order to disappear all terms except those related to the $f(0) = c_{i}$. The full derivation is as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} \sum_{a \in H}f(a) &= \sum_{a \in H}c_{0} + \left( \sum_{a \in H} \sum_{i = 1}^{|H|-1}c_{i}x^{i}\right) \\ &= c_{0} \cdot |H| + \left(\sum_{j = 0}^{|H|-1}\sum_{i = 1}^{|H|-1}c_{i}(\omega^{j})^{i}\right) \\ &= c_{0} \cdot |H| + \left(\sum_{i = 1}^{|H|-1}c_{i}\sum_{j = 0}^{|H|-1} (\omega^{i})^{j} \right) \\ &= c_{0} \cdot |H| + \sum_{i = 1}^{|H|-1} c_{i} \frac{1 - (\omega^{i})^{|H|}}{\omega^{i} - 1} \\ &= c_{0} \cdot |H| \end{aligned}$$.

Recall that for some $r$, the geometric series $\sum_{i = 0}^{n - 1} r^{i} = \frac{1 - r^{n}}{1 - r}$. Letting $r = \omega^{i}$, we see that the numerator of the geometric series evaluates to $0$, since $\omega^{i}$ is a $|H|$-root of unity and as such $(\omega^{i})^{|H|} = 1$. We avoid degenerate denominators by only letting $i \in [1, |H|-1]$.

We begin by noticing that any polynomial with degree less than $|H|$ has a unique decomposition with respect to the vanishing polynomial $\mathbb{Z}_{H}$. Recall that $\mathbb{Z}_{H}$ is simply the polynomial whose roots are elements of $H$ and therefore vanishes when evaluated anywhere on $H$. Specifically, there exist polynomials $g$ and $h$ such that

$$f = g + \mathbb{Z}_{H} \cdot h$$

where $\mathsf{deg}(g) < |H|$ and $\mathsf{deg}(h) < \mathsf{deg}(f) - |H|$. This allows us to reinterpret $\mathbb{I}_{sc}$ in a way that makes MSS relevant.

$$\sum_{a \in H}f(a) = \sum_{a \in H}g(a) + \mathbb{Z}_{H}(a) \cdot h(a) = \sum_{a \in H}g(a).$$

- $\mathcal{P}_{usc}$ computes $\hat{g}’, \hat{h}$, and $c_{|H|-1} \in \mathbb{F}$ such that:

- $\hat{h} \in \mathsf{RS}\left[L, \frac{D - |H|}{|L|}\right], \hat{g}’ \in \mathsf{RS}\left[L, \frac{|H|-1}{|L|}\right]$

- $\hat{f} = \hat{g}’ + c_{|H|-1}X^{|H|-1} + \mathbb{Z}_{H}\hat{h}$

- $\mathcal{P}_{usc}$ sends the econding of $\hat{h}$, $\hat{h}|_{L} \in \mathsf{RS}\left[L, \frac{D-|H|}{|L|}\right]$

- $\mathcal{V}_{usc}$ computes $\hat{p}(x) = \mathcal{E}\hat{f}(X) - \mu X^{|H|-1} - \mathcal{E}\mathbb{Z}_{H}\hat{h}(X)$.

- $\mathcal{V}_{usc}$ accepts iff $\hat{p}|_{L} \in \mathsf{RS}\left[L, \frac{|H|-1}{|L|}\right]$

Interestingly, by porting the SCP into the context of modules, the sumcheck strategy of binding variables to randomness can be abstracted to encompass folding arguments for openings to committments in various settings. Of course, when doing this, a number of adjustments must be made to ensure security.

Give visual of sumcheck arguments

| $\Pi_{msc}$ | $\Pi_{usc}$ | $\Pi_{tsc}$ | $\Pi_{csc}$ |

|---|---|---|---|

| $O(2^{w})$ | $O(n)$ | $O(n)$ |

$\mathcal{P}_{sc}$: SumCheck Prover

$\mathcal{V}_{sc}$: SumCheck Verifier

$\mathbb{I}_{sc}$: SumCheck Instance

$\Pi_{sc} = \langle \mathcal{P}_{sc}, \mathcal{V}_{sc}, \mathbb{I}_{sc} \rangle$: Interactive SumCheck Argument

$\mathbb{I}_{sc} = (\mathbb{F}, p, w, )$:

$\mathcal{B}^{w}$ : $w$-dimensional boolean hypercube

$\alpha \overset{c}{=} \beta$ : $\alpha$ is claimed to equal $\beta$

$(\mathsf{Comp}, \mathsf{Input})$: Computation and Input pair

$(\mathcal{C}, I_{\mathcal{C}})$: Circuit and Input pair

$\mathcal{L}_{sc}$: Sumcheck language

$\mathcal{L}_{C}$: valid assignments for compuation $C$

MSCP = multivariate sumcheck protocol, USCP = univariate sumcheck protocol, TSCP = tensor sumcheck protocol